Sensorimotor Stage (0 to 18-24 months)

At the beginning of this stage (0 to 7 months), children’s physical development is still in its early stages, and only allows them to interact with what is directly in front of them. Also, they have yet to develop the concept that even though an object is no longer seen, it still exists. That is why infants and toddlers are often amused by the game of peek-a-boo. When you cover you face, you literally disappear in the child’s mind. You magically reappear when you uncover it. Between 7 to 9 months, children start to develop the concept of Object Permanence, which is an important milestone in their development.They start to understand that even though an object is out of sight, that does not necessarily mean it is out of mind. This also marks the emergence of memory. As children continue to grow, they start to develop other more complex cognitive capacities.

-

Make Skittle Ripples and Sensory Bottles with SLP, Tiffany Chen -

Video #1: Send a Secret Message with ELG’s SLP, Tiffany Chen -

Get Slimed! Science and Speech Activity with Tiffany Chen

Preoperational Stage

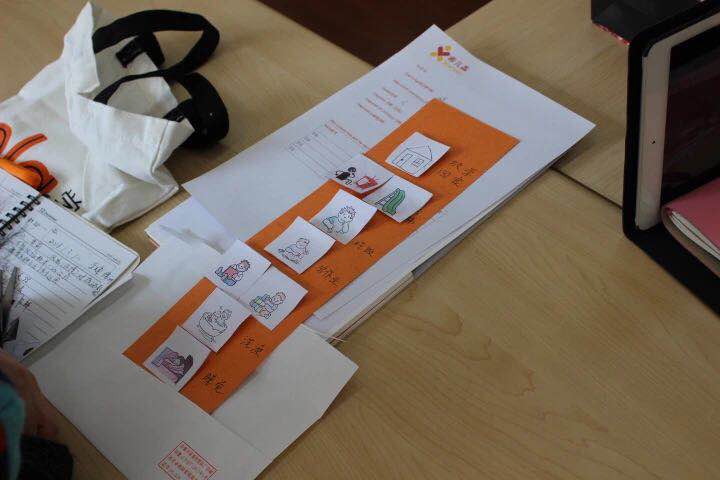

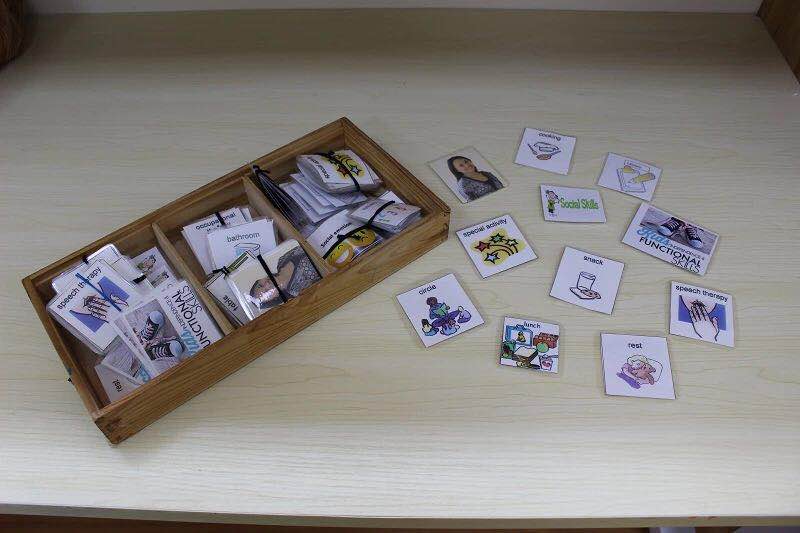

In the sensorimotor stage, children experience the world primarily through movement and sensory input. However, after the age of two, they start to develop more complex language, memory, and imagination. Instead of relying on external input and reflexes, they begin to process information internally. One of the hallmarks of this stage is the development of symbolic thought. This means children are able to use language and pictures to represent objects, instead of having to point to the object itself. They are able to create make-believe, such as imaginary friends, and to learn though pretend play.

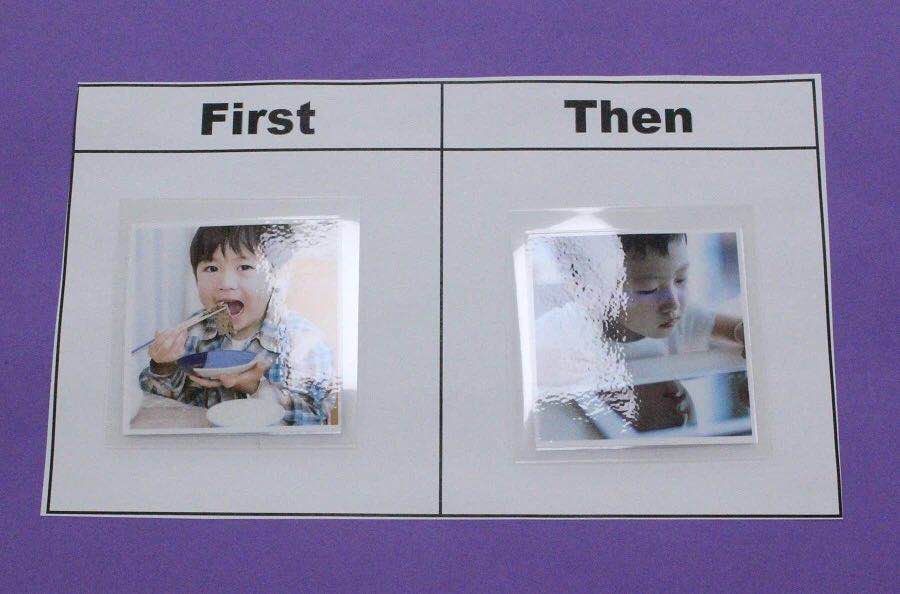

During this stage, children start to understand the concept of time, particularly the difference between the past and the future. Along with this, they start to develop a sense of cause and effect, and of comparison. As children reach the age for pre-school and kindergarten, we begin to see them developing the cognitive capacities needed for formal learning. However, during this stage, children have not yet fully developed the ability to think logically. For example, they may struggle to understand the idea of constancy. For instance, if you show children at the preoperational stage three containers with different shapes, they are unlikely to comprehend that they can contain the same quantity of water. Children at this age can also seem quite egocentric. This is because they can have difficulty understanding other people’s perspectives. They also tend to not be able to understand that situations, actions, or issues can be altered or reversed.

During this stage, play remains the primary way through which children learn. To support their child’s development, parents should continue to incorporate ample opportunities for children to learn through playing, particularly more symbolic play, such as pretend play and role play. It is useful to encourage them to use their imagination to create stories and scenarios. As children at this stage have not yet developed complex logical and analytical capacities, it is still too early to begin formal academic learning, such as mathematics or computer programming. Exploring these areas before children are developmentally ready can lead to frustration, and potentially to a dislike of the subject. Instead, children at this stage learn best by doing things and participating in various activities. To foster their learning, they should be encouraged to interact with things in their environment. During this process, it is useful for parents to ask children about their activities and give them the opportunity to come up with their own answers. The purpose here is not to having the child provide a “correct” answer, but rather to give them the opportunity to reflect and develop a habit of thinking about thinking, or metacognition. At this stage, it is also helpful to present children with new objects and encourage them to ask questions.

Concrete Operational Stage

Children start to enter school age during this stage. School becomes a major part of their cognitive, psychological, and social development. The major hallmark of the concrete operational stage is the development of operational thought, which means children are developing more logical and methodical manipulation of symbols. They are able to process information internally, which enables them to learn and solve problems without directly interacting with an object. Particularly, their understanding of categories, numbers, time, and space develop during this stage. Children also tend to become less egocentric as they develop the ability to understand other people’s perspectives. They also understand that their thoughts and feelings are unique to them, and may not apply to others. However, as suggested by the name, children’s thinking at this stage is quite concrete and literal. For example, they may have a hard time understanding abstract and hypothetical concepts.

To support their children at this age, parents should build upon their strengths and newly developed analytical skills by providing them with opportunities to categorize, build timelines, and classify information. Asking open questions, which start with ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘where’ and ‘how’, can encourage children to engage their reasoning and thinking. For example, brain teasers and riddles are effective and fun ways to foster analytical skills. Although children at this stage excel in concrete and inductive reasoning, such as mathematics, they still struggle with hypothetical concepts. Philosophy, politics, and morality may be difficult for them to fully understand. However, parents can start to introduce other abstract ideas, such as three-dimensional models or scientific experiments.

Formal Operational Stage

To support children’s learning at this stage, it is helpful for parents to offer step-by-step explanations and use charts and other visual tools. We should also encourage children to explore more hypothetical situations. We can begin to introduce broader concepts, such as the global political system. It should also be noted that as children and teenagers become more independent, their cognitive development also becomes more self-motivated. Parents may play a smaller role in their child’s development than in previous stages, however this does not mean they no longer contribute to it. Notably, socio-emotional development becomes a large component of children’s development during this stage, and parents play an important role in being attentive to their child’s psychological well-being.

Overall, children play an active role in their cognitive development. To foster their development, it is more effective to follow their developmental trajectory and provide what they need when they need it. Children and their brains have the instinct to learn. By understanding these developmental milestones and their child’s needs at each stage, parents can be more prepared to understand and support their child’s growth.

This is the second article in a two-part series by Dr. Davy Guo on Children’s Cognitive Development. Click here for Davy’s first piece on Introduction to Children’s Cognitive Development from Dr. Davy.